David Hodgson (artist)

David Hodgson | |

|---|---|

photograph by A.G. Stannard | |

| Born | 13 June 1798 |

| Died | 22 April 1864 (aged 65) |

| Nationality | British |

| Education | Norwich Grammar School; John Crome |

| Known for | Landscape painting |

| Movement | Norwich School of painters |

| Spouse | Frances Stone |

David Hodgson (13 June 1798 – 24 April 1864) was a professional English painter of landscapes and an active member of the Norwich School of painters. He was the son of the amateur artist Charles Hodgson, whom he accompanied on a tour of Wales in 1805, when he was seven. He was taught art by John Crome at Norwich Grammar School.

Hodgson never lived away from Norwich. As well as earning an income from the sale of his paintings, he was employed as a drawing master at the Grammar School, which allowed him to live a comfortable, if uneventful, existence. He was an accomplished painter of architectural subjects, and showed works on a regular basis at exhibitions in Norwich, London and elsewhere. His paintings have at times been confused with those of his father, as his artistic style did not develop significantly during his career. A leading member the Norwich Society of Artists, he was a strong advocate for the arts in Norwich, and a man who was popular with both his pupils and his fellow artists during his lifetime.

Background

[edit]The Norwich School of painters, which included David Hodgson, was a group connected by geographical location, the depiction of Norwich and rural Norfolk, and by close personal and professional relationships. The school's most important artists were John Crome, Joseph Stannard, George Vincent, Robert Ladbrooke, James Stark, John Thirtle and John Sell Cotman. It was a unique phenomenon in the history of 19th-century British art.[1] Norwich was the first English city outside London where such a school arose,[2] and it had more local-born artists than any subsequently-formed school elsewhere.[3] The city's theatrical, artistic, philosophical and musical cultures were cross-fertilised in a way that was unique outside London.[2][4]

Within the Norwich School was the Norwich Society of Artists, which arose from the need for a group of Norfolk artists to teach each other and their pupils. Founded in 1803, the Society was key in establishing the artists' associations with each other.[5][6] Its stated aims were "to conduct an Enquiry into the Rise, Progress and Present State of Painting, Archaeology, and Sculpture with a view to point out the Best Methods of Study to attain to Greater Perfection in these Arts".[7] It held regular exhibitions and had an organised structure, showing works annually until 1825 and again from 1828 until its dissolution in 1833.[8] The Norwich School's leading spirits and finest artists of the movement were Crome and Cotman.[9][1]

The impact of the Norwich School outside East Anglia was based largely upon the works of Vincent and Stark, who were seen as important members of the second generation of the school, and whose exhibited paintings in the capital attracted much praise in the London press.[10] This generation, which included David Hodgson, represented a shift towards the work of the mid-Victorian artists, who were less innovatory that those of thirty years earlier.[11] Vincent and Stark's connection with their home city was only occasionally noted, as the Norwich School was regarded at the time as being a provincial teaching centre.[10] Interest in paintings by the Norwich School declined during the 1830s, but the school's reputation rose after the Royal Academy's 1878 Winter Exhibition.[12] By the end of the century, it was regarded as belonging to a bygone age.[13]

Life

[edit]David Hodgson, the son of Charles Hodgson and his wife Nanny Chiswell from North Walsham, was born in Great Yarmouth on 13 June 1798 and baptised at the town's parish church on 18 June.[14][15] His father was a school master and amateur artist, who actively encouraged his son to develop his artistic talents.[14] Few details of David Hodgson's early life are known.[16] In 1805 the seven-year-old boy accompanied his father on a tour of Wales,[17] which included a stay in Chester and may have included a trip to Liverpool to visit relatives.[18] He attended Norwich Grammar School, where he was taught drawing by John Crome and mathematics by his father.[19] Like his father, he was a steady supporter of Crome, even comparing him artistically to Robert Burns.[20]

During Hodgson's adulthood, which was relatively uneventful, he lived in one parish, St. George's Tombland, in the centre of Norwich.[21] As an adult he returned to paint aspects of Chester on numerous occasions.[19] He succeeded Crome as the drawing master at Norwich School in about 1825,[22] and lived during his teaching career on Tombland, a street situated close to the school. His occupation necessarily limited his artistic output, but helped by the sales of his paintings, it allowed him a comfortable existence. He taught a number of pupils who were to become artists of the Norwich School of painters, and was apparently very popular with his pupils.[17][19]

Hodgson's portrait was painted in watercolours by Horace Beevor Love in 1831.[23] The portrait is kept by the Norfolk Museums Collections in Norwich Castle.[24]

Family

[edit]On 1 January 1823, Hodgson married Frances Stone at St George's Church, Tombland.[25] Her father Francis Stone (1769-1835) was an architect and the surveyor for Norfolk, whose achievements included the design of the County Asylum at Thorpe St Andrew. In 1831 they published The Picturesque Views of all the Bridges belonging to the County of Norfolk, with Hodgson's lithographs being based on Stone's drawings.[26]

A son, Francis Henry Stone Hodgson, was born on 2 December 1823. Three other children were born: Anna Maria (born on 31 August 1823), Sarah Anne Frances (born on 19 March 1826), and Josephine Amelia, who was christened in March 1830 but who died in infancy.[27] Anna Maria married Alfred George Stannard, himself from a family of Norwich School painters.[28]

In 1856 Charles Hodgson died in Liverpool,[14] and David Hodgson continued his father's practise as an art master at the Grammar School.[21][29] He moved from Tombland in the city centre to nearby Greyfriars' Lane, off what is now Upper King Street.[19][30]

His wife Frances died in August 1863, and he died at his home on 22 April 1864, and was buried in the churchyard of St. Bartholomew, Heigham.[31][32] He left an estate of several thousand pounds to his family. His only son, the Reverend Francis Henry Stone Hodgson, also died that year, on 20 September 1864.[33]

Artistic career

[edit]

Hodgson was one of the second generation of artists of Norwich School of painters, several of whom were trained by their own fathers, but who were also influenced by the work of later painters. Like his contemporary Henry Ninham,[34] he became an accomplished painter of architectural subjects, and the two artists complemented each other in this respect, but Ninham's oil paintings are considered to possess more finesse.[35] Along with Ninham he was the foremost illustrator of Norwich's architectural heritage following John Thirtle's death in 1839, but he took more interest than Ninham in depicting architectural ruins.[36] He is acknowledged as having made a substantial contribution to topographical lithography with his illustrations of the bridges of Norfolk (published in 1831), which were based on the drawings of his father-in-law Francis Stone.[37]

He exhibited his works on a regular basis at the Norwich Society of Arts and in other cities around England.[38][39] In Norwich, he exhibited 30 landscapes, one portrait, three figures, one still life and 75 architectural drawings, over a period of twenty years, out of a total of 114 works.[40] In London, he showed one painting at the Royal Academy of Arts, twenty-seven paintings at the British Institution and eleven paintings with the Royal Society of British Artists at Suffolk Street. The art historian Harold Day, who along with Andrew Moore has provided a detailed account of Hodgson's life and work, praised him for his depiction of the interiors of buildings.[19] The number of paintings he exhibited during his career was affected by both his professional career as a schoolmaster and the large number of his works that he sold to private buyers.[17] He received regular praise in the local press, for instance when the Norwich Chronicle praised his work as "promising", and on another occasion reported that he "demonstrated a lasting concern with problems of perspective".[41][42] His Norwich Fishmarket was the first of his works to receive critical acclaim in the press.[38]

In 1822 he became Secretary of the Norwich Society of Artists and played an important part in the running of the Society at a time when it was struggling without permanent premises with which to exhibit its works.[43] Along with Robert Leman and Thomas Lound, he started the Norwich Amateur Club whose aim to allow artists to practise their sketching skills,[44][45] and with Lound he revived the Artists' Conversaziones, in which artists met as friends to discuss their work.[46] First held on 21 January 1830, when Hodgson was made Honorary Secretary, the Conversaziones was finally wound up in 1839.[47]

In 1832, the year Hodgson began his employment as a drawing master at the Grammar School, the Duke of Sussex appointed him as his Painter of Domestic Architecture, an appointment which does not seem to have produced much financial gain for him in the form of direct patronage.[21] A visit to Ely in 1858 resulted in several paintings.[19]

Artistic and literary output

[edit]Hodgson mainly worked in oils and produced few watercolours of a high quality.[21] His sketches and watercolour studies were later used as the basis for future works.[48] Hodgson's paintings have at times been confused with those of his father, whose footsteps he followed, but whose works were of a less domestic nature than his son's.[49] The works he produced during the latter part of his career show little significant development in style from earlier works dating back to 1822.[19][50] They have been criticised for their poor colouring, for instance by Miklos Rajnai, who described his technique as 'clotted' and 'treacley' with a tendency towards yellows and browns.[48]

Hodgson's reputation rests upon his ability as a painter of oils, but not for his etchings.[36] These were influenced to an extent by John Sell Cotman,[16] and were also possibly influenced by George Cuitt (1774-1854), according to the historians Andrew Moore and Russell Searle.[36] The etchings of Henry Ninham are finer in quality,[51] and whilst Hodgson was technically accomplished, he lacked Cotman's skills and draughtsmanship.[36] In Searle's opinion, his outstanding plate is Sandlings Ferry from Antiquarian Remains Principally confined to Norwich and Norfolk, an etching that strikes him as "brooding" and being unlike that of any other by an artist of the Norwich School.[52]

Hodgson was more literary and articulate than many of his contemporaries.[34] His Lessons on Perspective were published in the Norwich Mercury on 20 July 1822,[48] he wrote an unpublished memoir about the life of his father, now kept in the British Museum, which outlined Charles Hodgson's career,[43] and he also had his own poetry published.[14] His letters to the local press included one to the Norwich Mercury dated 4 August 1858, about Norwich's civic portrait collection.[34] His surviving correspondence shows that he was a strong advocate for the arts in Norwich, and was among the first to write about the Norwich School of painters as an identifiable entity.[53]

He possessed excellent skills in perspective.[48] Andrew Moore described him as "a competent draughtsman and landscapist",[38] and the art historian Josephine Walpole described his The Octagon, Ely Cathedral , 1857 as an "almost incredible achievement".[14][54]

Some of his paintings now show signs of being badly affected by cracking, as do many of his generation of the artists of the Norwich School.[55]

Works

[edit]- Britton, John (1830). Picturesque antiquities of English cities: illustrated by a series of engravings of ancient buildings, street scenery, etc. with historical and descriptive accounts of each subject. various illustrators and engravers, illustrations of Norwich by David Hodgson. London: Longham. OCLC 83539403.

- Hodgson, David (1842). Antiquarian Remains Principally confined to Norwich and Norfolk. OCLC 656134492. Copies held at the Millennium Library in Norwich, and at the University of East Anglia. The plates, based on earlier sketches,[48] were in preparation for least five years.[36]

- Hodgson, David; Hodson, Francis H.S. (1860). A reverie: or, Thoughts suggested by a visit to the gallery of the works of deceased Norfolk and Norwich artists, August 20th, 1860. Norwich: Cundall, Miller, and Leavins, (printed for private circulation). Copies of this work are held at the Millennium Library in Norwich. The preface contains tributes by Hodgson to John Crome, Robert Ladbrooke, George Vincent, James Stark, John Berney Crome, John Sell Cotman and Charles Hodgson.[34]

- Hodgson, David; Stone, Francis (1830). Picturesque Views of all the Bridges belonging to the County of Norfolk. Engelmann, Graf, Coindet & Co. Archived from the original on 9 January 2019. Retrieved 11 June 2019.

Gallery

[edit]-

The Old Fishmarket, Norwich (1825), Yale Center for British Art

-

Market Place, Norwich (1842), Norfolk Museums Collections

-

The Nave of Norwich Cathedral, Norfolk Museums Collections

-

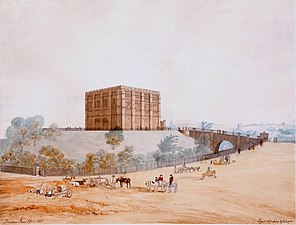

Francis Stone and David Hodgson, Norwich Castle (1833)

-

Interior of Norwich Cathedral (1838), Norfolk Museums Collections

References

[edit]- ^ a b Moore 1985, p. 9.

- ^ a b Cundall 1920, p. 1.

- ^ Hemingway 1988, pp. 9, 79.

- ^ Walpole 1997, pp. 10–11.

- ^ Hemingway 1988, p. 17.

- ^ Rajnai & Stevens 1976, p. 13.

- ^ Clifford 1965, p. 5.

- ^ Rajnai & Stevens 1976, p. 4.

- ^ Cundall 1920, p. 12.

- ^ a b Hemingway 1988, pp. 21–22.

- ^ Moore 1985, p. 118.

- ^ Hemingway 1988, p. 23.

- ^ Hemingway 1988, p. 30.

- ^ a b c d e Walpole 1997, p. 136.

- ^ David Hodgson in "Bishop's transcripts for Yarmouth", FamilySearch (David Hodgson) (registration required)

- ^ a b Walpole 1997, p. 138.

- ^ a b c Dickes 1905, pp. 204–206.

- ^ Day 1968, p. 193.

- ^ a b c d e f g Day 1968, p. 200.

- ^ Dickes 1905, p. 205.

- ^ a b c d Clifford 1965, p. 46.

- ^ Sutton 1967, p. 34.

- ^ Moore 1985, pp. 119, 147.

- ^ "Portrait of David Hodgson (drawing)". Norfolk Museums Collections. Retrieved 10 June 2019.

- ^ "England Marriages, 1538–1973". FamilySearch. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. (registration required)

- ^ "Francis Stone". Grace's Guide to British Industrial History. Retrieved 5 November 2018.

- ^ "England Marriages, 1538–1973". FamilySearch. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. (registration required)

- ^ Moore 1985, p. 104.

- ^ Walpole 1997, p. 139.

- ^ "NORWICH O/S Map 1884". Norwich Maps. Norwich Heritage. Retrieved 11 June 2019.

- ^ "British Newspaper Archive, Family Notices". FamilySearch. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. 17 July 2018. (registration required)

- ^ Moore 1985, p. 121.

- ^ "Find a Will (Hodgson/1864)". UK Government.

- ^ a b c d Moore 1985, p. 119.

- ^ Moore 1985, pp. 118, 123.

- ^ a b c d e Searle 2015, p. 81.

- ^ Searle 2015, p. 122.

- ^ a b c Moore 1985, p. 125.

- ^ Walpole 1997, pp. 137–138.

- ^ Rajnai & Stevens 1976, p. 140.

- ^ Norwich Chronicle, 8 August 1818.

- ^ Norwich Chronicle, 29 July 1820.

- ^ a b Moore 1985, p. 47.

- ^ Walpole 1997, p. 116.

- ^ Dickes 1905, p. 206.

- ^ Walpole 1997, pp. 119–20.

- ^ Dickes 1905, pp. 368–69.

- ^ a b c d e Moore 1985, p. 120.

- ^ Cundall 1920, p. 30.

- ^ Moore 1985, p. 51.

- ^ Moore 1985, p. 123.

- ^ Searle 2015, pp. 81, 83.

- ^ Moore 1985, pp. 47, 119.

- ^ "David Hodgson: The Octagon, Ely Cathedral, 1857". Artnet Worldwide Corporation. 2018. Retrieved 11 June 2019.

- ^ Moore 1988, p. 154.

Bibliography

[edit]- Clifford, Derek Plint (1965). Watercolours of the Norwich School. Cory, Adams & Mackay. OCLC 1624701.

- Cundall, Herbert Minton (1920). The Norwich School. London: Geoffrey Holme Ltd. OCLC 1356134.

- Day, Harold (1968). East Anglian Painters. Vol. II Norwich School. Eastbourne, UK: Eastbourne Fine Art. ISBN 978-0-902010-00-0.

- Dickes, William Frederick (1905). The Norwich school of painting: being a full account of the Norwich exhibitions, the lives of the painters, the lists of their respective exhibits and descriptions of the pictures. Norwich: Jarrold & Sons Ltd. OCLC 558218061.

- Hemingway, Andrew (1988). The Norwich School of Painters, 1803-33. Oxford: Phaidon. ISBN 978-0-7148-2001-9. (registration required)

- Moore, Andrew W. (1985). The Norwich School of Artists. HMSO/Norwich Museums Service. ISBN 0-903101-48-3.

- Moore, Andrew W. (1988). Dutch and Flemish painting in Norfolk. London: HMSO/Norwich Museums Service. ISBN 978-0-11-701061-1.

- Rajnai, Miklos; Stevens, Mary (1976). The Norwich Society of Artists, 1805-1833: a dictionary of contributors and their work. Norwich: Norfolk Museums Service for the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art. ISBN 978-0-903101-29-5.

- Searle, Geoffrey Russell (2015). Etchings of the Norwich School. Norwich: Lasse Press. ISBN 978-0-9568758-9-1.

- Stone, Frank; Hodgson, David (1840). "Picturesque Views of All the Bridges Belonging to the County of Norfolk in a Series of Eighty Four Prints in Lithography from Drawings by F. Stone and Son". British Library. Retrieved 5 November 2018.

- Sutton, Gordon (1967). Artisan or Artist?: A History of the Teaching of Art and Crafts in English Schools. Oxford: Pergamon Press. ISBN 978-1-4831-9408-0.

- Walpole, Josephine (1997). Art and Artists of the Norwich School. Woodbridge: Antique Collectors' Club. ISBN 1-85149-261-5.

External links

[edit]- 591 works by (or relating to) David Hodgson Archived 9 January 2019 at the Wayback Machine at the Norfolk Museums Collections, including

- Hodgson's prints Archived 9 January 2019 at the Wayback Machine for Britton's Picturesque Antiquities of English Cities (1830)

- prints Archived 9 January 2019 at the Wayback Machine for Picturesque Views of all the Bridges belonging to the County of Norfolk (1830)

- 21 prints by David Hodgson at the British Museum

- Works by David Hodgson sold at auction according to Invaluable